Throughout the course of creating Plane/Sailing, I have learned a lot about the various packets and formats involved with tracking aircraft, ships and amateur radio users. This page is a Frequently Asked Questions list, but I’m not exactly a guru people come to for answers—really, this is a list of questions I’ve asked, and answers I’ve found, while developing the system. If you are creating a similar system for yourself, I hope this list helps to summarise and explain the key points of all these various packets and messages. Certainly if this page had existed when I started writing code, it would have been a whole lot quicker!

Questions

- How can we Track Aircraft?

- What’s an Extended Squitter?

- What’s ADS-B?

- What’s Comm-B?

- What’s Multilateration (MLAT)?

- What’s Dump1090?

- What are the Common Formats of Mode S Data?

- What are Feeders?

- What Different Identifiers do Aircraft Have?

- How can we Determine Tail Numbers, Aircraft Types, Operators etc?

- How can we Track Ships?

- What’s rtl_ais?

- What AIS Data is Available?

- What’s the Common Format for AIS Data?

- How can we distribute AIS Data?

- How can we Track Amateur Radio Users?

- What are APRS and AX.25?

- What are rtl_fm and Direwolf?

- What are Common Formats for APRS Data?

- What are Callsigns, SSIDs and Symbols?

- What’s an iGate?

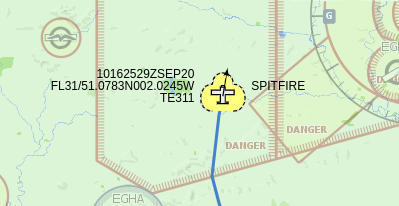

How can we Track Aircraft?

I can see five already, this shit is easy

I can see five already, this shit is easy

In the beginning (1950), there was radar. A typical air traffic control radar spins around, emitting radio-frequency waves. These bounce off a target and return to the radar installation. The known angle of the dish, combined with the measured time for the pulse to get back from the plane, gives a range and bearing to the aircraft. This is great for tracking aircraft in a horizontal plane, but rubbish at determining their altitude, and it has no way of identifying any particular plane.

As the skies got busier, the “secondary radar” concept was developed to help solve this problem. Along with the “primary” radar that simply bounces radio-frequency waves off a target, secondary radar uses a transponder within the aircraft which sends out a short burst of data containing information for air traffic control. The secondary radar installation emits a signal at 1030 MHz, and the transponders reply at 1090 MHz, with messages such as “Mode A”, which encodes a squawk code identifier for the aircraft, and “Mode C”, that encodes the altitude. Great! Air traffic controllers could now see altitude and identify individual planes.

The skies got busier again. With so many aircraft in the air, a new method was required where the radar installation could selectively (hence “S”) query certain aircraft, rather than sending out a signal and have every aircraft reply at virtually the same time. Alongside this new capability, Mode S was designed to carry much more data (up to 112 whole bits!) for future capabilities.

Every aircraft in UK & EU airspace has a Mode S transponder, and it’s the Mode S replies (that is, what the aircraft are sending back to the radar installation) that we receive and decode. So the aircraft aren’t really talking to us, but we can hear what they are sending out.

Every aircraft. No exceptions.

Every aircraft. No exceptions.

There’s an excellent write-up of the history and implementation of these protocols at The 1090MHz Riddle, and some additional information about idents/squawk codes here.

What’s an Extended Squitter?

It’s what happens the morning after you drink five pints and eat a vindaloo.

No, alright. Mode S was designed to send more data, and be more flexible, than Mode A & C before it. It has a concept called a “downlink format”, which says what kind of message it is. Some of these are equivalents to the old formats, so DF4 provides altitude, and DF5 provides the squawk code.

DF17 and DF18 are what’s known as “extended squitter” messages, which are like expansions to the Mode S format. Within DF17 and DF18 messages, a further identifier called a type selector says what kind of data is encoded, so these extended squitter messages can be used to carry many different types of data alongside those specified by the main Mode S downlink formats.

There’s a good table here.

DF19 is a military extended squitter. We don’t go there, it’s a silly place.

DF19 is a military extended squitter. We don’t go there, it’s a silly place.

What’s ADS-B?

ADS-B is one of the main uses of those extended squitter Mode S messages. It takes the Mode S transponder system to the next level, allowing aircraft to transmit many types of data in their response, including latitude & longitude, heading, speed, the status of their autopilot, and much more.

It’s this data on which Plane/Sailing largely depends.

ADS-B contains its own subset of messages, each identified by a type selector, and with the restriction to 112 bits per message, each one contains only a small amount of information. In order to build up the full set of information, latitude and longitude must be received in one message type, along with altitude in another, heading and speed in another, and so on.

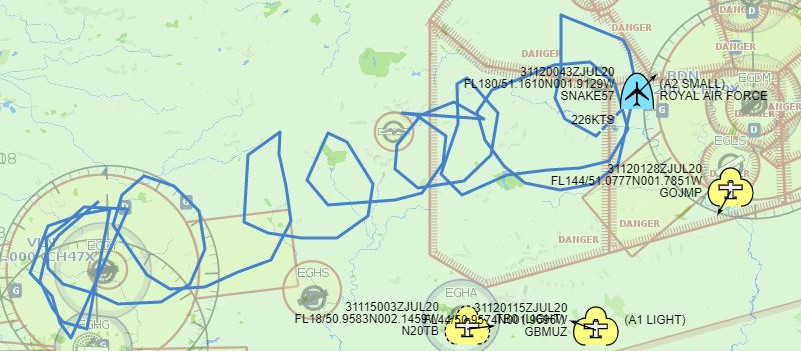

Since the introduction of ADS-B on most aircraft, and so many planes in the air that it’s easy to see something wherever you are, it has been easy for hobbyists to buy a simple software defined radio and antenna, tune to 1090 MHz, and start tracking aircraft.

That’s a lotta planes.

That’s a lotta planes.

What’s Comm-B?

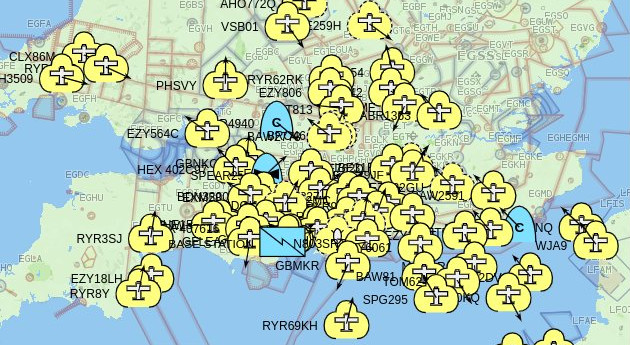

Leaked footage from the Mode-S Downlink Formats planning meeting (xkcd)

Leaked footage from the Mode-S Downlink Formats planning meeting (xkcd)

Along with ADS-B Extended Squitter messages with DF17 and 18, Comm-B is another similar set of Mode S messages using DF20 & 21. These contain at the top level some basic data such as altitude and squawk, much like the old Mode A & C or Mode-S DF4 & 5. However, they also contain an extra payload that contains useful information. This can include the aircraft flight number/callsign, and in fact some aircraft only send their callsign this way, and not using the equivalent ADS-B message. (This callsign is Base64 encoded, but in what will become a recurring theme in this page of fitting alphanumeric callsigns into fewer bytes than you might expect, not using the same characters everyone else uses for Base64 encoding.)

The contents of the extra payload of a Comm-B message can include various things, based on the Comm-B Data Selector (BDS), which is similar to the type selector in ADS-B. However here there is an additional complication in that the BDS is only sent in the Comm-A message from secondary radar installation to the aircraft. The reply does not always indicate obviously what it is. As an amateur monitoring station, we therefore sometimes need to infer what type of message it is in order to decode it, since we can’t see what the radar actually asked for.

Now Plane/Sailing is of course only tall by virtue of standing on the shoulders of giants, and thus far the OpenSky libadsb Java library has provided all the code required to decode Mode-S and ADS-B messages until now. Comm-B data, apart from the basic altitude and squawk identity, are not yet supported. So at this point I had to do some of my own decoding within Plane/Sailing. As always, The 1090MHz Riddle comes through with the full details.

What’s Multilateration (MLAT)?

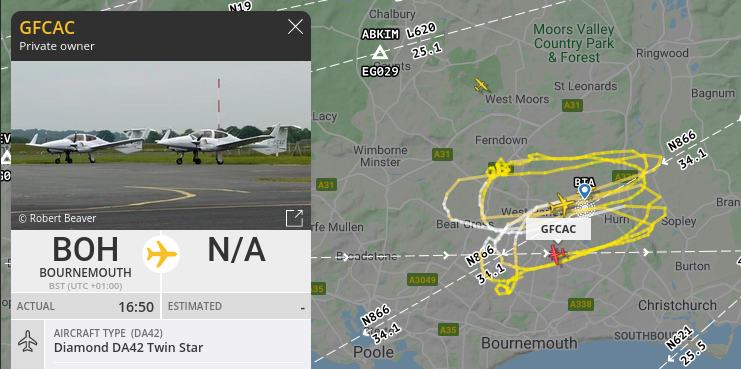

Although all aircraft in UK & European airspace have Mode S transponders, not all are equipped with support for ADS-B, which is a specific set of messages within the Mode S framework. This means that some aircraft provide identifiers and an altitude, but never any more information than this, unless you happen to have a primary radar of your own. However, if you go onto a (largely amateur tracking) website like FlightAware and look up one of these aircraft, you’ll see it has a position!

Websites such as FlightAware can provide position fixes for these aircraft using an approach called multilateration, or MLAT. This takes advantage of the fact that there are many receivers detecting and decoding Mode S information for any one aircraft. Provided these receivers have synchronised clocks, their time of packet reception can be measured very accurately, and used to determine the position of the aircraft via triangulation. Each individual receiver knows what time it received a message from the aircraft, and when the server puts that together with two or three others, factoring in the speed of light, the position can then be estimated.

In the description of Plane/Sailing I make a point to say that it uses your own radios, and isn’t pulling publicly available tracking data from sites like FlightAware, Marine Traffic and aprs.fi. However, here’s where the waters get muddied. Because that MLAT data is only calculated server-side, we actually do rely on FlightAware to provide this. This data is provided back to the client, in a “synthetic extended squitter” format, i.e. it looks just like “real” ADS-B position and velocity data received from the radio. This can then be ingested into Dump1090 and Plane/Sailing… almost!

Again we hit a minor speed bump in that the libadsb library has almost everything it needs to decode these messages, but not quite! Until libadsb supports them, I implemented a work-around in Plane/Sailing’s code to interpret the MLAT messages properly.

What’s Dump1090?

Dump1090 is a piece of software that decodes 1090 MHz signals from a software defined radio dongle, or other radio receiver, and provides that data out in a number of formats, described below. It’s also capable of receiving MLAT data from a server as well, and provides a web-based interface called “SkyAware” by which the user can view all the aircraft it’s tracking. Other applications are available for doing this job, but Dump1090—and the FlightAware version of it in particular—is by far the most common.

The SkyAware web interface uses JSON to fetch the data from the processing software. In version 1 of Plane/Sailing, our web interface queried that JSON directly, but in version 2 we switched to using own back-end server that communicates with Dump1090 using other formats.

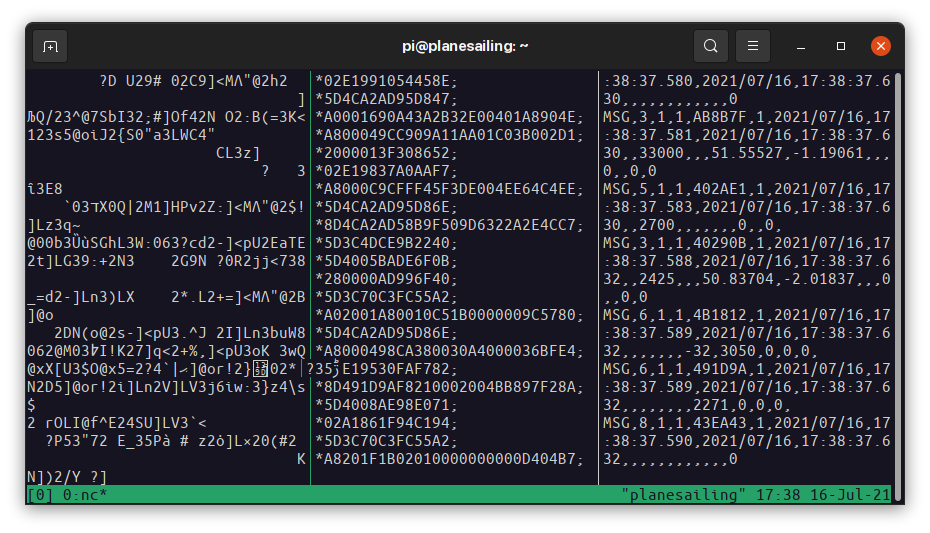

What are the Common Formats of Mode S Data?

So, we have established that Mode S uses 56-bit or 112-bit payloads, with a number of header bytes and a checksum. Great, how do we tap into that data coming out of Dump1090? Well the short answer is, we can’t.

Dump1090 supports three different output formats which are de facto standards for sending Mode S/ADS-B data around a network, but none of them are quite the raw bytes.

Two are named after the Mode S Beast that pioneered them.

- The Beast Binary format is what the vast majority of applications, including Plane/Sailing and feeders such as PiAware, use for their data. It consists of an

0x1aescape character, a message type byte, a timestamp, a signal level byte, then the actual Mode A, C or S bytes themselves. The fact that it contains a timestamp is key to its use in multilateration, as it preserves the time the time at which the message was received. Dump1090 provides a TCP server on port 30005 for this data. - The Beast AVR format is the raw data bytes converted to hexadecimal. Each packet starts with an asterisk, then the hexadecimal bytes, finishing with a semicolon, carriage return and line feed. There’s no additional information here like timestamps or signal levels. Dump1090 provides a TCP server on port 30002 for this data.

- The SBS/BaseStation format is human-readable and looks similar to a CSV file or NMEA-0183. It’s very easy to use, but unfortunately does not contain all the data that’s available in the other formats. Signal strength is not included, and neither are aircraft categories. Dump1090 provides a TCP server on port 30003 for this data.

Plane/Sailing supports all three formats, though Beast Binary is preferred. It uses OpenSky’s adsblib to handle the Mode-S messages in Beast format.

Dump1090 also writes its internal data out to a JSON file, which is what its own web interface picks up. This isn’t exactly a common standard format, but it’s what Plane/Sailing v1 used to get aircraft data, and Plane/Sailing v2 continues to support it as an option.

What are Feeders?

“Feeders” provide data from your radio receiver to websites that track aircraft, like FlightAware and FlightRadar24. They all (as far as I know) expect to receive data in Beast Binary format from software such as Dump1090, and they then provide that to their server. The server aggregates this information from all over the world, providing a global display of aircraft tracks. They also provide user-submitted content such as photographs of each plane.

Some of these servers do multilateration calculations for aircraft without ADS-B capabilities, and not only use the results for their own displays, but provide them back to the client as well. For example PiAware, which feeds FlightAware, provides its MLAT data in Beast Binary data back to Dump1090 on port 30104, and provides an additional server for this same data on 30105 that Plane/Sailing taps into.

What Different Identifiers do Aircraft Have?

Aircraft have a number of different identifiers, which you may see in Plane/Sailing, Dump1090, FlightRadar24 and other software. They are:

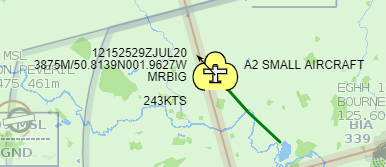

- A 24-bit address for the specific aircraft and is globally unique. You’ll often see this formatted as a six-character hexadecimal value, like “4CAFD0”. Each Mode S message contains this 24-bit code, so it’s ideal for use as a unique ID. ICAO manages the system and grants each country a block of addresses that it can then assign to aircraft. In some countries, these are algorithmically related to the aircraft registration, but in others they’re not.

- A registration, or tail number, which also identifies a specific aircraft and is globally unique. This is painted on the side of the aircraft and is usually five letters, like “G-JZHG”. The prefix identifies the country of registration, e.g. “G” for Great Britain. It’s not transmitted in any Mode S message. Some countries allow vanity tail numbers…

MRBIG: Sex & the City fan, insufferable dick, or both?

MRBIG: Sex & the City fan, insufferable dick, or both?

- A flight number, or callsign, which is based on the operator and route. This will usually be globally unique at any given time, but an aircraft may change flight numbers, e.g. when it is sold or moved to a different route. It’s usually letters followed by numbers, like “BA731”. This is what air traffic control will use when talking to the aircraft. There is an ADS-B message that provides this information. If an aircraft belongs to a private individual it likely won’t have an operator-based flight number, so the tail number will be used instead as the callsign.

- An ident, or squawk code, which is assigned by air traffic control and set by the pilot. It’s a four-digit number like “7123”, and can be changed for certain reasons, e.g. there are special squawk codes for emergency situations. At any given time, many aircraft will share the same squawk, though they should be unique within a single ATC’s airspace. This is available from Mode A, Mode S and ADS-B messages.

How can we Determine Tail Numbers, Aircraft Types, Operators etc?

You may recall from the previous section that tail numbers are not transmitted in ADS-B at all, and yet when look at an aicraft on Plane/Sailing or other websites you’ll often see the tail number listed. Likewise, nothing in ADS-B indicates the type of an aircraft (beyond a broad size category) or the operator. So how do we determine these?

The answer is: databases.

The OpenSky database and Dump1090’s internal JSON database both contain a mapping of ICAO 24-bit addresses to tail numbers and aircraft types with a reasonable level of coverage, along with manufacturer, operator and owner information for a smaller subset.

Plane/Sailing uses a customised version of these databases, along with its own mapping of flight number prefixes to operators (e.g. “BAW” -> “British Airways”) to provide more information than can be obtained from ADS-B alone.

How can we Track Ships?

Step 1, pick a sunny weekend and wait for the yachties to emerge.

Step 1, pick a sunny weekend and wait for the yachties to emerge.

In the beginning, there was radar. (Sound familiar?) Most ships and shore stations such as Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) centres have radar, but it has its limitations for example in tracking vessels that are close together, or in heavy rain. It also provides no way of identifying each ship.

AIS is a data system much like ADS-B but for ships, which is used to report data like identity, name, position, course and speed in order to improve safety at sea. Unlike Mode S and ADS-B, AIS transponders aren’t triggered by ground-based secondary radar; instead all AIS transponders transmit on their own schedule using techniques like SOTDMA and CSTDMA to avoid talking over each other.

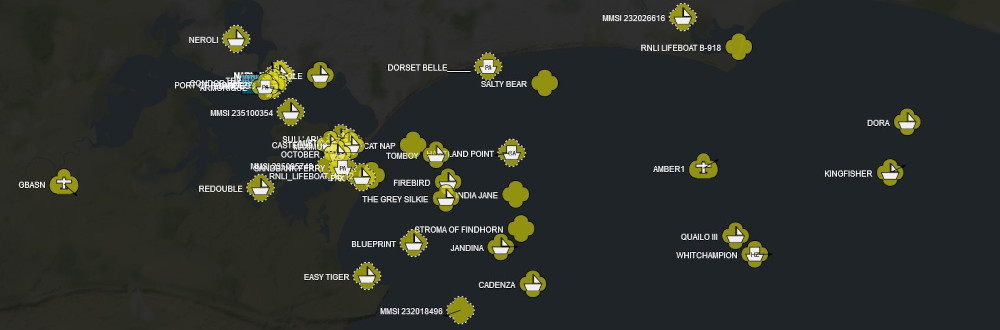

Not all seagoing vessels have AIS. Larger ones are required to carry the more powerful Class A AIS transponders, while smaller vessels may carry Class B, or nothing at all. So unless supplemented with a radar, an AIS system will not be tracking small sailing dinghies, only larger yachts and ships.

What’s rtl_ais?

rtl_ais is similar to RTL-SDR’s rtl_fm software, but it not only demodulates audio from the RF data coming from the dongle, it also decodes the data packets from both AIS channels at the same time. It’s a simple command-line utility that should work automatically without much configuration. It outputs AIS data in the standard NMEA-0183 protocol over UDP.

What AIS Data is Available?

The AIS protocol contains within it around two dozen separate message types, which contain different information and can be transmitted at different rates. Furthermore, Class A and Class B transponders have their own message types, as do shore stations, aids to navigation, etc. Much like ADS-B, the receiver must aggregate data from many different messages in order to build up the full set of information about a vessel.

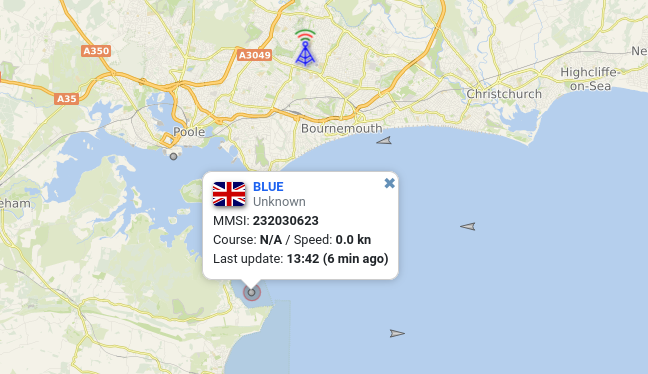

Each vessel is identified by its MMSI, a numeric value that is globally unique and assigned when a radio licence is granted to the vessel. Every message contains this MMSI, along with the other information for that message type.

Vessel names are also transmitted via AIS, but only in message types 5 & 24, which are not typically transmitted as often as those containing position, course and speed. That’s why you’ll often find Plane/Sailing showing a track for “MMSI 123456789” with a known position and other data, but the vessel name hasn’t yet been received.

What’s the Common Format for AIS Data?

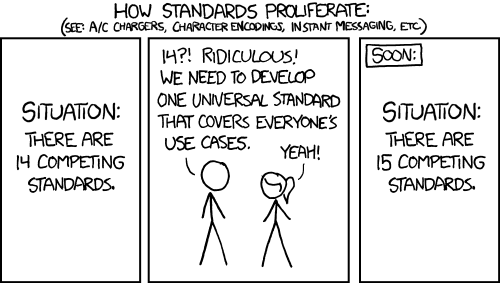

Leaked footage from the NMEA-0183 AIS planning meeting

Leaked footage from the NMEA-0183 AIS planning meeting

NMEA-0183 specifies a human-readable, comma-separated serial data format. If you’ve ever worked with GPS devices, it will look familiar to you:

$GPGLL,3751.65,S,14507.36,E*77

There’s a header identifying the message type, a latitude, longitude, and a checksum. All NMEA-0183 messages are designed to be human-readable like this… except one.

!AIVDM,2,1,1,A,55?MbV02;H;s<HtKR20EHE:0@T4@Dn2222222216L961O5Gf0NSQEp6ClRp8,0*1C

!AIVDM,2,2,1,A,88888888880,2*25

AIS is essentially a binary format paying lip service to the NMEA format, encoding itself with Base64—but not with the same characters everyone else uses for Base64, or the ones Comm-B callsigns use for Base64—and allowing a single AIS message to span across multiple NMEA-0183 messages.

This is pretty crazy, and frustrating for anyone trying to understand the messages without the aid of parser software, but that’s what we’re stuck with. We use tbsalling’s aismessages library to handle this data.

How can we distribute AIS Data?

Unlike the aircraft tracking world, where each tracking website comes with its own dedicated client application you have to install, the ship tracking world is a little more low-tech. When you sign up for a site like Marine Traffic, you are essentially given an IP address and a port to send your NMEA-0183 data to over UDP.

Now rtl_ais can only send to a single UDP port, so in order to send that data to multiple locations (Plane/Sailing, Marine Traffic, AIS Hub etc.) we need to re-send the data in multiple UDP streams.

Although you could achieve this simply with a combination of command-line utilities such as tee and ncat, the commonly used software for this is AIS Hub’s AIS Dispatcher. As well as providing the basic functionality of receiving UDP messages on one port and sending them out to several others, it performs useful additional functions such as downsampling. In recent years it’s also been given its own web interface for configuration and a map display.

Version 1 of Plane/Sailing used the undocumented ability of AIS Dispatcher v1.2 to save a KML file of its data, and our web interface queried that file directly. More recent versions of AIS Dispatcher have removed that feature, which is one of the reasons we moved to having a Plane/Sailing server that could receive data in the standard NMEA format.

How can we Track Amateur Radio Users?

Figure 12. The Domain of a Nerd

Figure 12. The Domain of a Nerd

APRS is a system for transmitting small packets of data, often including positions, used by amateur radio hobbyists and some weather stations. Although Hams with APRS transponders in their cars are not a common sight, I added support for them to Plane/Sailing to complete the set—since we are tracking air and sea, why not land too?

What are APRS and AX.25?

APRS can be extended to transfer all sorts of information, including user-to-user messaging and email, what we’re interested in for Plane/Sailing is APRS transponders that are reporting their position. APRS packets are broadcast by convention on 144.8 MHz in Europe, although the frequency varies in different areas. Plane/Sailing receives and decodes these messages, and if any contain information useful to us like position, course and speed, these are recorded in the system.

The APRS network is aided by a system of digital repeaters, or “digipeaters”, that receive and rebroadcast APRS packets up to a certain number of “hops”. Where radio amateurs have installed these digipeater systems high up with good line of sight, APRS tracks can be received not just from the local area but from much futher afield.

APRS is built on top of a data transfer protocol called AX.25, and much like an ancient modem, data at (usually) 1200 bits per second is converted into audio, which is then modulated onto the VHF carrier. The reverse process at our end turns the VHF signal back into audio, then back into binary data.

What are rtl_fm and Direwolf?

Traditionally, the job of encoding and decoding AX.25 packets was done by a dedicated hardware device known as a Terminal Node Controller (TNC). With modern technology, the job can be done in pure software.

The two parts of this software decoding puzzle are rtl_fm and Direwolf. rtl_fm takes the radio frequency input and demodulates it to an audio stream. Direwolf then takes that audio stream and decodes AX.25 packets from it, which typically are APRS. Direwolf has many more functions than this, for example it can operate as a transmitter, digipeater, iGate and more, though in this project we are only really interested in the receive side.

What are Common Formats for APRS Data?

In the air, APRS packets conform to the APRS spec (PDF). Each packet consists of a number of fields, such as source and destination addresses, the addresses of the digipeaters the message has passed through, and the payload of the message. And just as with ADS-B and AIS, there are a number of different APRS payloads that provide different information.

Each source and destination address is an up to 6-character callsign, and an up to 2-character SSID, so the field length is naturally… 6 + 2 = 7 bytes.

Also, we hope you like Base 91, ‘cos that’s what we got.

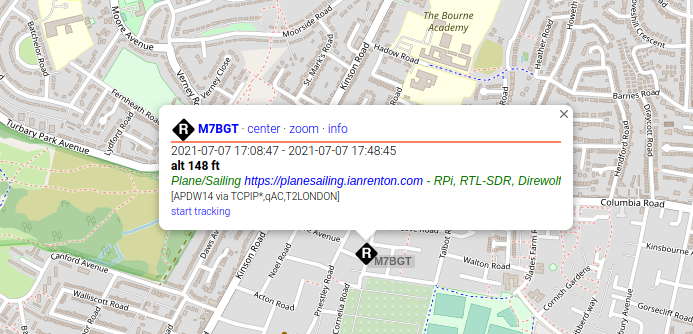

Now when Direwolf is set up and receiving these packets, you will notice it logging some roughly human-readable lines like this:

[0.2] G8CHQ-9>UQPPSP,WIDE1-1,WIDE2-1:`wQ4prA>/`"5>}_)<0x0d>

MIC-E, normal car (side view), Yaesu FTM-100D, Off Duty

N 51 00.3000, W 001 53.2400, 55 MPH, course 237, alt 427 ft

That first line shows the decoded source, destination and digipeater callsigns, followed by the Base 91 encoded payload. The other two lines then provide the decoded data from the payload. So how do you get access to a stream of this data, e.g. for Plane/Sailing? Of course… you can’t.

Direwolf’s actual output formats are KISS and AGW, which replicates the output of AGWPE. Of these, KISS is the more common and the one we use for Plane/Sailing.

KISS takes the binary bytes of an APRS AX.25 packet, and simply wraps them with some extra bytes that indicate the start and end of frames, and provide some command codes that are useful for transmission. In our receive-only code, it’s fairly easy to ignore all of that and just parse the AX.25 packet within for APRS data. Plane/Sailing uses ab0oo’s javAPRSlib to do this parsing.

What are Callsigns, SSIDs and Symbols?

APRS uses Amateur Radio callsigns, but extends them with the concept of “SSIDs” which describe the type of installation that is transmitting. For example an SSID of 0 is commonly used for home receivers and transmitters, while 9 indicates a car, and so on.

While the SSID can be used to determine a symbol to display (and Plane/Sailing does this), there is also a dedicated symbol field in APRS messages that provides a larger table of options to choose from, in case you want your symbol to be e.g. a car with a number superimposed on it.

What’s an iGate?

As well as direct point-to-point APRS transmission, and repeating via digipeaters, a common use of APRS is to receive data and upload it to an internet service, or APRS-IS. Much the same as FlightRadar24 for aircraft and Marine Traffic for ships, sites like aprs.fi aggregate the APRS data sent to them by “iGates” to provide a global picture of APRS tracks.

Add a Comment