A new amateur radio activity for this year that you may not be aware of is the “52 Week Ham Radio Challenge”. Coordinated via the website and via a Mastodon bot, it provides 52 challenges for 2025, approximately one a week, for players to work on alongside each other.

The first four weeks’ challenges were:

- Create a QSL card design

- Monitor as many NCDXF IARU beacons in one week as possible

- Work another continent on 80m or 160m

- Research the history of your callsign

If you’d like to take part, head to the website for the rules and if you have a fediverse account, to see how to track your progress using the bot. There’s no need to do them in a specific order or wait until a specific week, but it’s fun to do the same activities alongside others, and the bot regularly shares people’s progress.

Here’s how I got on with weeks 1 to 4!

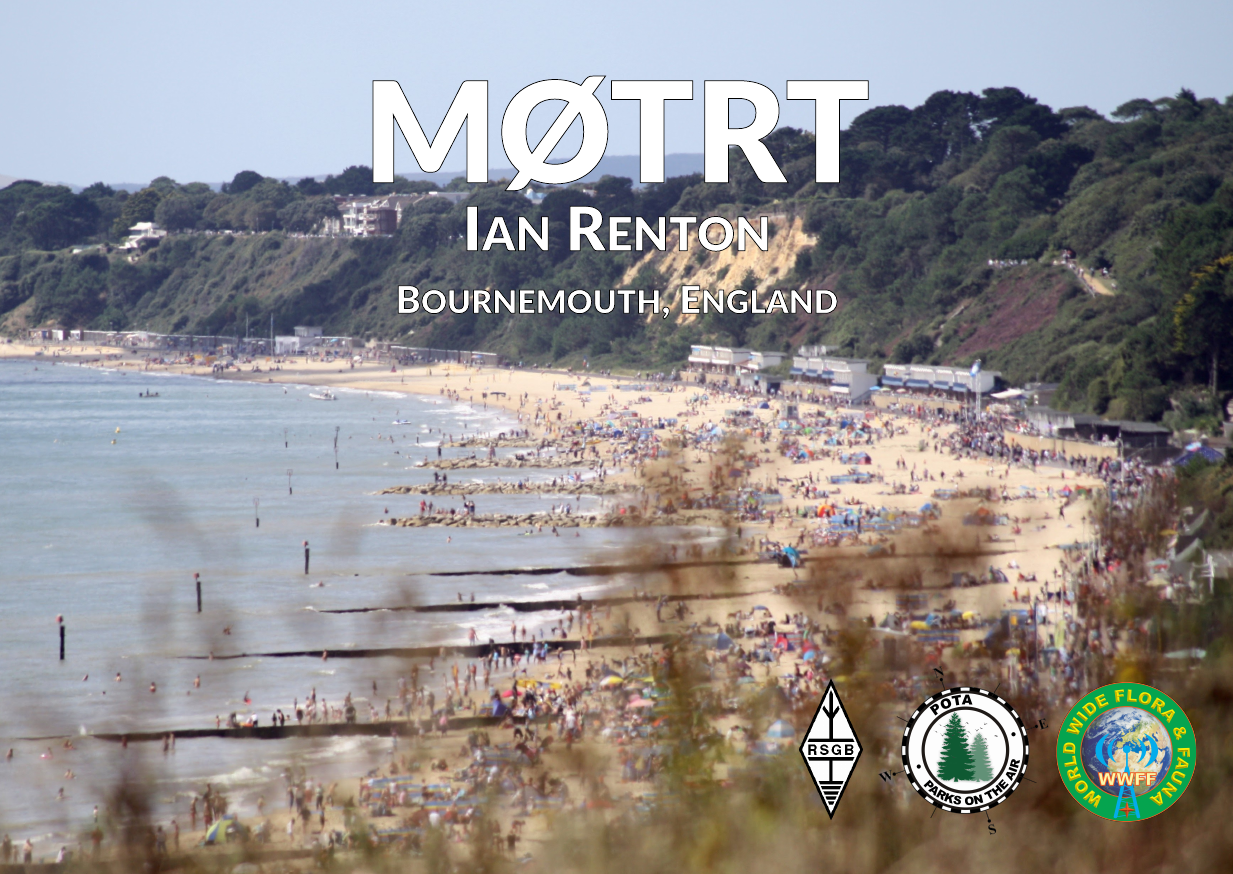

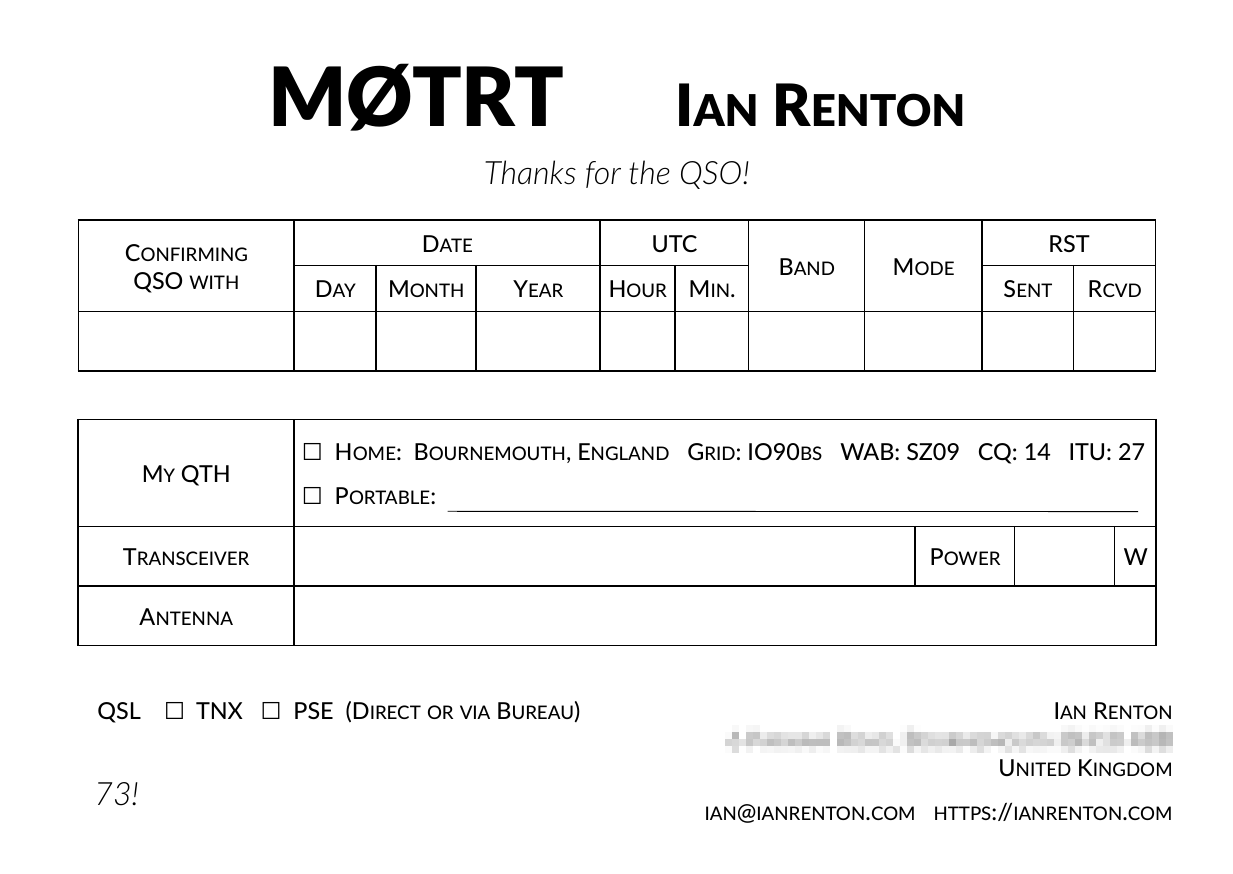

Week 1 (1-5 Jan): Create a QSL card design

This was one I had been putting off for ages, so I’m glad it came up! Physical QSL cards are rarely done anymore, and especially not for my main activities (POTA/WWFF and playing with digimodes), but I would love to receive one someday and would love to start sending them on request too. I did register with the RSGB QSL bureau in case Scout troops wanted to do QSL cards for Jamboree on the Air, but no-one asked and none came, which is a shame.

Still, it’s good to be prepared with a design that I could print in case I receive one or someone requests one, so week 1 of the challenge was a good excuse.

I started by researching the available printing services, both bespoke QSL cards such as UX5UO print and QSL Concept, and general postcard printing services like Vistaprint. My main goal here was to figure out the size, resolution and formats that would be required.

For a typical A6 card of 148mm by 105mm, printers typically ask for a few millimetres of “bleed” area around the design, to ensure no white edges are left when the cards are cut. I therefore designed my card to the 151 x 108mm size recommended by a number of services. Colour front and black & white back (like a typical postcard) seems to be a common setup, so I designed around that as well, ensuring that the photo I chose for the front was at 600dpi for a high quality appearance in print.

For the front I chose one of my favourite shots of Bournemouth beach, as I always like to see photos on QRZ/HamQTH of where others live, and hopefully the recipients of my QSL cards would like to see where I live as well. I included the logo of the RSGB alongside those of Parks on the Air and World-Wide Flora & Fauna to represent my main ham radio interests.

On the back, I included all the usual QSL details, along with a space to write in details of portable operations since that’s my main activity.

This was the result:

I’ve not yet sent these off to a printer, but might do soon. Then the long wait for someone to ask for one or send me their own begins!

Week 2 (6-12 Jan): Monitor as many NCDXF IARU beacons in one week as possible

This was a challenge I was less keen on. It’s great that these beacons are out there, and live monitoring of propagation conditions is very cool, but I didn’t find it a lot of fun to be listening to the noise for 10-20 minutes at a time in the hope of picking out a quiet burst of Morse code that’s too quick for me to copy properly. The beacons only operate on the 20 metre band and up, so by the time evening came and I have some time for radio, the bands were closed and I heard almost nothing. I think I heard the occasional blip from CS3B, but that’s it.

However, midweek I spotted a post by Paul PA3DSB which mentioned the Faros software by Alex VE3NEA. I decided to try that out instead, leaving it running during the daytime to see what it could pick up.

This was much more successful than listening by ear in the evenings, and the History function provided a nice way to visualise how propagation on the higher bands varied during the day.

![]()

Overall it looked like I was getting decent daytime reception of CS3B, OH2B, 4U1UN and 4X6TU on 20 metres, with the higher bands appearing mid-morning and tailing off through the afternoon as you would expect. All bands up to 10m came in, as winter during a peak solar activity year is a good combination for the higher hands, although of course winter gives us less time to play on them before dusk takes them away again.

I also saw very occasional receptions of RR90, VR2B, ZS6DN and LU4AA on certain bands only, which I definitely would never have found without Faros doing the work for me!

The NCDXF beacon map is shown below, annotated with a green tick for beacons I received well, a brown tilde for beacons I received less well but at least once during the day, and a red cross for those I did not receive at all.

![]()

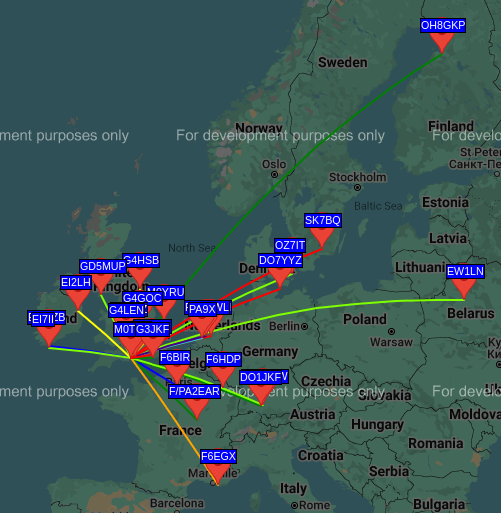

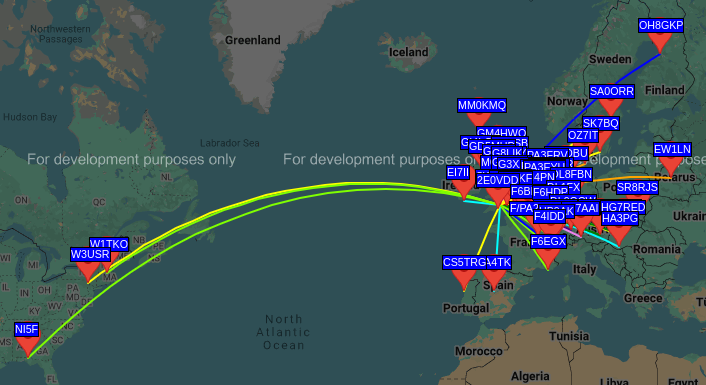

Week 3 (13-19 Jan): Work another continent on 80m or 160m

This was going to be a tricky one. I don’t have an antenna resonant anywhere longer than 40 metres, and trying to tune my home end-fed random wire antenna to 80 or 160 resulted in a sequence of unhappy noises and a “high SWR” warning.

In theory of course, home-made antennas are cheap for any band, and there was nothing stopping me buying some wire, heading out into the woods in the middle of the night and building myself a huge antenna. Nothing except a total lack of time and energy, anyway. Massive respect to those who did!

Luckily the notes for this challenge did specify: No antennas? Hear another continent on those bands. You can use a WebSDR!

If listening was good enough, I could at least make an effort from home in the evenings when time allowed. Not having worked these bands before, I didn’t really know what to expect in terms of range, only that if DX QSOs could be had then it would be at night.

On Wednesday 15th, I tuned around the bands just after local sunset at around 1700z. On 1933kHz I heard what seemed to be a local net on the Isle of Wight with a ham from Scotland joining in, and I copied G7JVF, G4RZQ and GM6XFI. I could hear nothing else above the noise on either band at that time.

On Thursday 16th, I tried later at around 2200z. At this time 160m seemed dead, but over on 80 I picked up DA0WWA on 3777kHz and a PA3 station that I could not fully copy on 3760kHz. Still no DX.

I decided to dedicate a solid block of time to the endeavour on Friday, from 2215z until 2245z. European WWA stations were out in force again allowing easy reception of their high power transmissions, along with some of their callers, but sadly still no DX stations were received.

In my half-hour monitoring period I heard the following.

- 3648kHz: DA0WWA, DD1SB and F5TVG

- 3708kHz: French ragchew, could not copy callsign

- 3751kHz: German ragchew, could not copy callsign

- 3765kHz: 9H1TT and ON8EI

- 3769kHz: SN7WWA and LZ2AFQ

- 3778kHz: EG3WWA and SP2DUS

The following morning I got up at 0630z and scanned through the bands before dawn, but was disappointed again with very little audible on the lower bands.

Either I wasn’t staying up late enough, or the bands just weren’t in good enough shape for me to pull DX out of the noise with just my dodgy ears. With time running out for this week, I decided that I would ditch the romantic image of a radio operator huddled over their gear late at night, and instead go for an approach similar to week 2. All I needed was to receive another continent at some point on 80 or 160m, and in the spirit of the beacon “listening” challenge it didn’t really matter if that was with my ears, or even if I was sat at the station at the time. It was time to break out the big guns, and one of my oldest loves on the HF bands: WSPR.

WSPR was the first “digimode” I ever tried, before even the ubiquitous FT8. I was fascinated by the use of narrow bandwidths, extremely slow symbol rates, and digital signal processing to pull out signals many decibels below the noise floor. Even more so when I did my first meagre 5W transmission and was immediately received in Australia.

So on Saturday night I left WSPR running, and… still no DX?!

Sunday night rolled around and I repeated the test… but received no DX again.

In a last ditch effort, recalling the Ham Challenge instructions, “You can use a WebSDR!”, that’s what I resorted to in the end. Around 0630z Monday morning, I “borrowed” a nearby KiwiSDR belonging to G8JNJ (thank you!) and finally received W1TKO @ -25dB, W3USR @ -25dB and NI5F @ -18dB.

I’m calling this challenge a success on a technicality, but it’s not one I feel good about. Still, it’s the first time I have tried “operating” on either of the lower bands, so it’s been a learning experience for sure.

Week 4 (20-26 Jan): Research the history of your callsign

This is one of the easier challenges, and unfortunately my callsign has no obvious history.

MØ calls have been issued to Full (and the older Class A) licencees since 1996, giving only a 20-year period over which the call could previously have been issued.

I do wonder if the call had a previous owner before me, because MØTRT was “suspiciously” available. When picking my new callsign, I took a list of assigned ones published by Ofcom, and subtracted them from the list of all possibilities to produce a list of what was available. This showed that the vast majority of calls were taken until those whose three letters started with X, so the block was almost fully assigned, and new “automatic” assignments would be of the form MØX??. But MØTRT was an outlier, still available even though automatic assignments would have passed it several years ago. It sounded good out loud and in Morse code, so I grabbed it.

But that’s my only clue that MØTRT may have had a previous owner. Perhaps their licence expired or they applied for a new vanity callsign in the mean time, freeing up their old call. A web search for MØTRT only provides results related to me, so if a previous holder of the call was active, they don’t appear to have made an impact online.

Ofcom have previously said in response to Freedom of Information requests that they don’t keep historical data for the list of assigned callsigns, only the latest, and information about recent previous holders would presumably be covered by GDPR anyway. With any previous holder being recent enough that I won’t find them in historic callbooks, I don’t believe there’s much more I can do to find out if there was a previous MØTRT out there somewhere.

The last part of the Ham Challenge prompt for this week was “In how far does your callsign indicate your geographical location?”. A UK M or G callsign without a regional locator as the next letter would previously have indicated England. However, as of last year the rules about regional locators were changed to make them optional, so while most hams from other countries in the UK still use them, in theory MØTRT could now be anywhere in the UK.

That’s it for this round-up, see you at the end of February for weeks 5 to 8!

Comments