Not long after my post about the game DJ Rivals, I finished the main part of the game and hit a metaphorical wall. There was no more story; I’d bought every item in the store and mastered the game’s hardest moves. The game tries to offer replay value via progressively harder missions based on those earlier in the game, and via battles against human players of comparable level. The latter offers nothing to play for apart from in-game money, which I already had in abundance, while the former offers only the elusive carrot of 100% completion, which dangled too far distant for me to want it much.

So I stopped playing – which is probably fair enough. I’d played it, enjoyed it, finished it and stopped. But it got me thinking about the number of games I’ve played that don’t end.

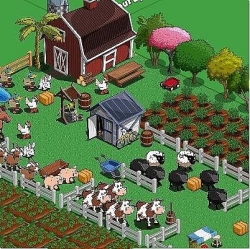

Zynga’s Farmville is perhaps the most well-known example I could give. At the beginning, the game is about designing a nice farm, planting the most efficient crops, coming back to harvest them and planting some more. This is fun. Then it’s just something you do. Then it’s annoying. Then you start contemplating spending real money on in-game items to automate the process. At this point it’s clear that planting and harvesting crops is not the game – the game is having a bigger and better farm than your friends. And the only way to achieve this, assuming you weren’t lucky enough to start first, is to be more devoted to the game or spend more real money than your friends do. (It shouldn’t surprise you that these are both things that make money for Zynga.)

A case of escalation of commitment (or commitment bias) can kick in, whereby the player has invested enough effort in the game that even though they are no longer enjoying it, they can’t bear to quit. And this only gets worse over time, because unlike most non-social games, Farmville and its kin don’t have an ‘end’. There’s no story to finish, and because the makers of the game can easily add more, higher-level items to acquire or quests to fulfill, there is no 100% completion to aim for. You quit, or you play forever.

I am no better than the rest as regards being sucked into these games. Tactics in Battle Stations only extend as far as clicking a button and upgrading your airship within one of a few effective builds, yet my character made it to level 85 before I quit, realising that the rate at which new shiny equipment was added to the game outstripped the rate at which I could acquire it. Starfleet Commander is a good strategy game in its own right, but after having reached the end of the tech tree, I found nothing worthwhile to aim for. The same flaw has turned me off Backyard Monsters at level 36, too.

Moreover, all of these games suffer from a time delay mechanic that increasingly is enough to put me off a game (Dungeon Overlord, for example) all by itself. Now, part of the aim of all these games (from the creators’ perspective) is to get users returning regularly to play – and view ads. To achieve this, every game I have mentioned – and countless thousands of others – have in-game activities that take time of the order of hours or days. This, I think, is my main problem with them.

In the vast majority of traditional computer and console games, there is a concept of a gaming “session”. The player sits down to play the game, plays continuously, and stops when he or she is done. But the majority of the new breed of social games aren’t like that.

They begin with a rush of activity, much like other games. You put the first few buildings down in your base, plant the first few crops, start and finish researching technologies within a few minutes. At some point, you choose to stop. But the game hangs its carrots just out of reach. “Sure,” it says, “you can stop. But your building is only half an hour from being finished. And once it’s finished, you’ll be able to do this and this, and build this, which only takes a few hours…”

In the early stages, it grabs you back when you might prefer not to be playing. Later on, by contrast, it switches around to perhaps the more annoying mode. More advanced things tend to take longer to build, research, grow, or whatever – possibly many days. So you’ll sit down for your gaming session, you’ll do your five minutes of formulaic clicking, harvesting your crops, planting new ones, then… then you stop. You can’t do any more; you have to wait two days before you can play again. In two days, you spend five more minutes clicking the same things, then stop again.

Once upon a time, I enjoyed these Facebook games, and I thought I still did. But yesterday, I logged in to do my five minutes of clicking, and realised all of a sudden that it was exactly the same five minutes of clicking I had done the day before and the day before that. I was grinding towards a non-existent goal, performing mindless tasks in search of a sense of completion that I knew would never come.

I thought, “why am I doing this?”, and it dawned on me that I didn’t have an answer to that.

I love playing games, and presumably always will. But I think I, and possibly others, need to get better at judging the enjoyability of games in this casual, social age. Certain kinds of game and certain games companies are now remarkably good at exploiting sunk cost and commitment bias, and in order to only play games that we enjoy, we should evaluate the game better, and decide earlier when it may be time to quit.

Comments