“All I’m doing is building stuff,” they say.

“That’s what Minecraft is good for, isn’t it?” I reply. “It’s like Lego with infinite pieces.”

“Yeah,” they say, and turns back to the computer screen; back to the childhood task of creating the new.

I turn back to the washing up that I was in the middle of, back to my adult role of cleaning and tidying and preserving that which already exists.

It feels odd to be writing about Minecraft in 2014. Following its 2009 “alpha” release, it quickly became the darling of the indie gaming world. There’s not a lot to say about it that hasn’t been said by countless reviewers and bloggers over the intervening years. I’d played it myself a few times—I made my character wander around, mine some rocks, fight some monsters, craft a few things. But I never “caught the bug”. That’s the all-too-adult brain at work again—I looked at the landscape and appreciated it for what it was, not what it could become.

Today though, for the first time, I saw Minecraft through the eyes of a child.

Raised on a self-imposed diet of videogames since they were old enough to shake a Wiimote, our kid has never had the enthusiasm for Lego that I did at his age. While I would disappear to my room for an afternoon to build, they always wanted to spend it with gamepad in hand. On occasion I despaired for the coming generation. I worried that their entertainment had become so pre-packaged and targeted that they wouldn’t want to create their own games. How could silent, limited, awkward Lego sets compare against a million man-hours of Nintendo’s finest creators delivering pure entertainment?

But now I sit and watch a child at work, and I know how wrong I was.

As night falls, the character flies up over the landscape and looks down to behold all that he has created. Torches spread out across the world like the fires of a nascent civilisation, casting light upon those things that human hands have built.

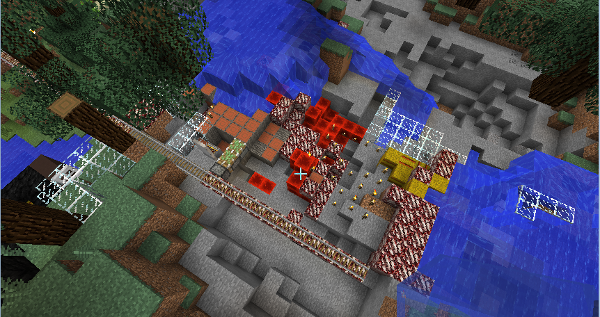

There are houses, now, where once there was only grass. Some of the roofs are made of coal and supported only by bookshelves and hay bales, but they are houses nonetheless. They are dry when the rain pours outside. There was a bed for the character to rest in, but now there are more than a dozen—for the character’s parents, siblings and cousins, they explain.

There are railways that connect them over fragile bridges far from ground. There is a torchlit tunnel beneath the surface, joining the houses of the tiny village to the woods where sheep and cows roam. There was a spider that “freaked them out”, so their character started to carry a sword with him at all times.

The environment, once wild and random, was being tamed.

Then they noticed that water would flow if the ground around it was removed. The great lakes of the world could be channeled. The tunnel became a great underground river, bringing water near to the houses of the people.

He built a black-lined room carved out of a hill, and decorated each block with a torch.

“It’s a Christian place,” they explain. “My character is a Christian.”

I had just watched that nascent civilisation invent religion.

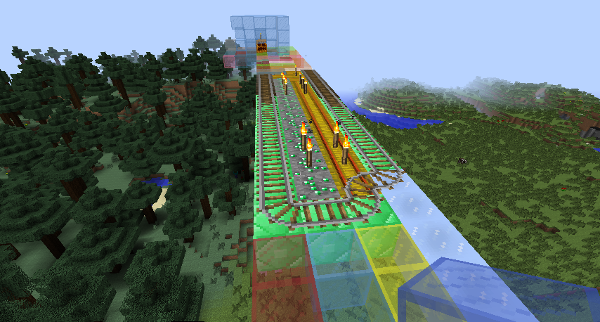

Dawn breaks. Among the high forest canopies there now stands something else—a tower, built on lowlands but rising taller than the hills. It is a vast structure of stone and glass and, for some reason, pumpkins. It is not built the way an architect would build, but nor does it look like a work of nature. It is the work of an almighty creator not restricted by principles of gravity or shearing moments. It is not utilitarian; not a house or a bridge or a water channel. It is something that was built just because it could be built.

The land was tamed, now; the world mastered. And so the one-man civilisation had reached for the stars.

I am no longer under the illusion that neat, rail-roaded videogame adventures will leave us a generation lacking the desire to create for themselves.

They may not spend their afternoons building Lego cars, but that’s okay. Within the last four hours I’ve watched them take a world of random-seeded entropy and transform it into a place where bridges of stained glass tower over the skies.

I think our children’s generation will be just fine.

Comments