I’ve spent much of the last few months resolutely not commenting on the NSA spying scandal, Edward Snowden, PRISM and all the other revelations that have been published by the Guardian and the New York Times recently.

While 99% of the population continue without knowing or caring what the implications of the spy programmes are, the revelations have caused a surge in the number of people telling the world — largely online, for irony’s sake — how stunned they are that their trust has been violated by the spy apparatus of their state.

Here’s the “tl;dr” version for all the busy novice cypherpunks out there, and you’re not going to like it: You should not have expected privacy in the first place.

Before I go further, I’ll address the obvious riposte to that — that in the US, the Fourth Amendment prevents the state from spying on its own citizens, and the NSA is clearly in violation of this. But other states have no restrictions whatsoever on spying on Americans. Is it any better to be spied on by GCHQ? What about China? The NSA does not have a monopoly on massive electronic dragnets.

So here’s the long version. If you feel like there should be a secure way of communicating online without state security apparatus knowing and recording it, this is the magnitude of the task you have ahead of you.

- Do you use popular, proprietary software? It’s compromised. Microsoft Windows, for example, has contained an NSA crypto key in all versions released since 1999.

- Do you use popular online services? They’re compromised. The PRISM scandal highlights the big players involved: Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Yahoo, the list goes on.

- Do you use professional cryptography products, or the hardware crypto capabilities of modern processors? Compromised.

- Do you or your ISP use popular network hardware? Compromised..

- Does your traffic flow through the UK or US? Compromised.

- Use Free / Open Source Software? Congratulations, your system is probably more secure. “Probably”.

- A big shout out to all the Ubuntu users who feel good about themselves now. It’s a good job you don’t run any proprietary graphics drivers, right?

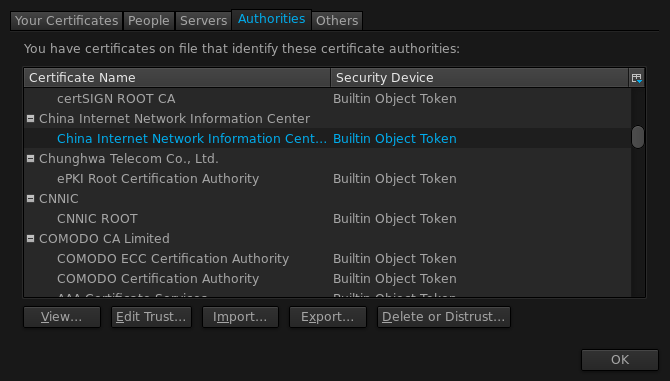

- Get the warm fuzzies when you see that little padlock icon in your browser? I hope you’ve reviewed your browser’s Certificate Authority list and made sure none are hacked or in bed with the Chinese government.

- Have you gone the extra mile, using only Tor darknet sites to ensure your privacy? Compromised.

-

More broadly, have you communicated by unencrypted phone, fax or e-mail at any time since the 1960s? Compromised.

- But do you communicate only by Triple-DES & Blowfish encrypted semaphore to your fellow cypherpunks in Faraday cages beneath Sealand? Congratulations, your communication is probably secure. “Probably”.

The fact of the matter is, if you trusted that your communications were safe from the national security apparatus of a state, particularly your own, you were almost certainly wrong. For privacy fans like myself, the sad news is that countries always have and always will invest vast amounts of time and money on building and maintaining their surveillance capabilities. Large companies will always be given incentives or demands to assist the state in which they operate. And there is very little that the individual privacy-conscious citizen can do about it.

If you want a guarantee of absolute privacy, you must trust every algorithm you use, every piece of hardware and software that handles your data, and everyone you communicate with. But you don’t.

Somewhere, somehow, your communication system is compromised.

Maintaining your privacy online is simply a matter of risk management — for each of the possible vectors by which your privacy could be compromised, which do you care about, and which can you do something about? If you’re an international diplomat with a Huawei 3G dongle, are you being spied upon by China? If you’re a Fourth Amendment nut, does the government read your Facebook? If you’re a business traveller, is your host’s network searching your email for company confidential information?

Assess the privacy risks and manage them. Don’t insist on absolute privacy, or you will find yourself unable to communicate with anyone. And don’t pretend absolute privacy was something you ever had.

Comments